The whole photographic industry is set to disappear, swallowed up by the giant squid that is information technology.

Cameras themselves are an endangered species, as a separate item, and with them camera shops, photography magazines, those irritating envelopes offering free films, everything. The whole industry. Kaput.

Imaging will not stop, of course. It will simply become a standard function of various forms of computer.

No one will need a camera when your mobile phone, pen, glasses, binoculars and even jewellery all have high-resolution cameras concealed inside.

The process is already well under way, with the arrival of the camera phone.

Suit-wearing analysts turned their noses up at camera phones when they first arrived, saying the picture quality was not good enough and the price was too high, and, well, they were just too trivial for serious people to worry about.

Ha! According to Canalys camera phone sales are rocketing ahead at 166 per cent per quarter, and 3.8 million of them were sold in Europe, the Middle East and Africa in the second quarter of this year.

Imaging specialist Future Image is already predicting that worldwide sales of camera phones could exceed all cameras, both digital and film, by the middle of next year.

New markets for digital cameras

And it will not stop there. Digital cameras are now so small, so powerful and

so cheap they are appearing in unexpected places.

Take the esoteric world of birdwatching. Until now, photographing birds involved heavy investment in fast SLRs with lenses the size of Kylie Minogue.

Twitchers have now discovered that if you strap an ordinary digital camera to a telescope with masking tape, you can use the zoom to frame the image and get a picture as good as professional chemical gear.

The extraordinary depth-of-field of digital makes this possible. The interesting thing about this development is that birders are adapting digital cameras as an adjunct to their scopes. It is the scope they regard as essential, and the camera as an optional extra.

Already, telescopes and binoculars with built-in digital cameras are becoming available. Soon, no twitcher will bother with a separate camera.

Same with astronomy. Amateur stargazers are ripping the casings off webcams, strapping the sensors to their telescope eyepieces and getting stunning results.

Here, the crucial new element is that an event can be snapped 10 or 100 times, and the results combined with software to form a pin-sharp final image.

Again, telescopes with built-in imaging are beginning to appear. The subversive iwantoneofthose.com is even selling a pen with a digital camera built in, although I haven't managed to figure what legitimate use this might have.

The IT takeover of photography is also being driven by the popularity of web photo services such as Funtigo and Ofoto (a subsidiary of Kodak, a company that has shown surprising agility in moving from chemicals to cyberspace).

The web is brilliant for this. Holiday snaps can be uploaded from Ibiza, edited in the basic way that 99 per cent of us need (i.e. cropped and with the redeye removed) and made available for all our friends and relations to look at.

But the not-so subtle extra feature is that Mum and Dad, who like to have proper photos they can look at and pass round while sitting on the sofa at family parties, can order prints and have them delivered through the post.

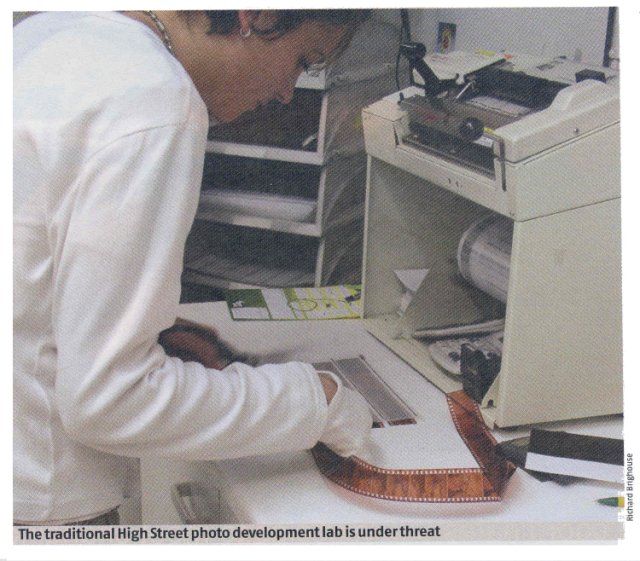

Or you can order your wedding snaps to be sent to everyone on your list. And the cost is very similar to your High Street minilab, only you don't have to go there twice, once to drop off the film and again to pick up the prints.

In short, the entire process has been transferred from the chemical industry and the retail trade to the IT industry, plus a bit of logistics.

Kodak is also aiming to chop the legs from under the minilab operators with its spiffy new photokiosk, where people can print off the snaps they take with their phones or indeed their digital cameras.

It looks like a printer with a touchscreen - you just select the pics you want to print, send them off either by infrared or Bluetooth, choose the format you want and press the button. And then, a few seconds later, out come your pics.

And where are these minilab-killing gadgets to be located? Boots? Jessops? No - Carphone Warehouse. Where teenagers shop.

Boots is where old people go to pick up their Phylosan, corn plasters and holiday snaps. The minilab operators are set to grow old with their current client bases while the youngsters print out their snaps at gadget shops.

Of course, resolution and low-light ability is going to have to improve before camera phones replace real cameras. But this is already happening: two-megapixel phones are already on the Japanese market and phones with zoom lenses are on the way.

Ultimately, cameras, minilabs, photographic shops and the rest of an entire industry are set to go the way of the typewriter. And the IT sector will hardly notice, only complaining about the amount of data traffic it is suddenly being called upon to carry.

Kodak profits are gone in a digital flash

Eastman Kodak last week posted a 63 per cent drop in third-quarter profits. It

was the latest low in a three-year slump in sales of camera film.

The company has not been slow to get into digital technology, but progress has been less than easy.

Kodak slashed its annual dividend by 72 per cent to bankroll a major shift away from its ailing conventional film business and into the fast-growing but highly competitive digital arena.

The company expects more than $1bn in digital imaging sales this year.

In 2004, industry analysts think film less digital cameras will begin outselling traditional film cameras for the first time.

But revenue from Kodak's photography division fell

$1.01bn in the US alone, even while consumer digital cameras sales surged 117

per cent.